Professor of Landscape Design at UC Berkeley and MacArthur Genius award-winner Walter Hood from Hood Design Studio stands out as a luminary force with his creation of the hilltop park on Yerba Buena Island, a sprawling 5-acre expanse offering panoramic views of downtown San Francisco and the Bay. Hood helmed the design of this park, an essential element of Yerba Buena Island’s green space where people can connect with nature, history, and each other.

“The hilltop park will give residents and visitors alike a new perspective in which to experience and understand the San Francisco Bay landscape. The island’s ecological and built cultural history serves as a new aperture to honor the site’s history as well as its new beginning.” – Walter Hood

In conversation, Hood radiated a warmth that mirrored his deep passion for his craft. As a 30+ year resident in the Bay, his unwavering interest and commitment to combining culture, history, architecture, and landscape shine through every thoughtful answer. Mr. Hood’s talent for designing story-rich spaces that seamlessly blend with the surroundings is evident–although it’s clear that he finds the most joy in the art of making places for people.

Tell us more about your background. What inspired you to pursue a career in landscape architecture?

Walter Hood: Well, I didn’t start in landscape architecture, I started out in architecture. Then, as an undergraduate, I was introduced to landscape architecture, and it caught my attention because it was much more artful than architecture. When I was introduced to landscape, it was more about people and the place where they live, versus architecture, which was much more abstract and less about the collective and individuals. I wanted to be in this place where I could have an impact on more people.

You were recently elected as a new member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences – congratulations! What does becoming a member mean to you?

WH: It means that I am now enshrined in the same place as George Washington, Jefferson Kang, and MLK Jr. (Laughs) A lot of the early founders thought that while democracy is paramount to a nation, there is an equal need for artists to give beauty to the world. It’s an amazing group to be with, to know that your contributions have been noted, and to know that you’re part of this larger think tank. It’s pretty powerful!

Can you talk about your first encounter with Yerba Buena Island?

WH: When I first moved to the Bay Area, Yerba Buena Island was known as where the Bay Bridge connects to San Francisco. I remember the first few months I was here, I would always go park my car, sit there, and just look at the city in wonder because you’re almost at eye level– it had the best view of San Francisco. When friends came to visit, I took them there. When I came on board on the hilltop park project, I could choose the sites I wanted to work on, and I wanted the island. As we started to work on the island, we began to learn about the layers of history that once stood there–the native inhabitants, then the early colonial people, the goat hill during the gold rush, and then the military. I’m interested in really finding the palimpsest of a place, and this island was just perfect because it had all of these layers. That was the attraction and still is the attraction for me–finding a way to preserve the site’s history while also maintaining a forward-looking perspective, without erasing its past.

Can you paint a picture of the “palimpsest” – how visitors might read the layers of that history as they walk through the park you’ve designed?

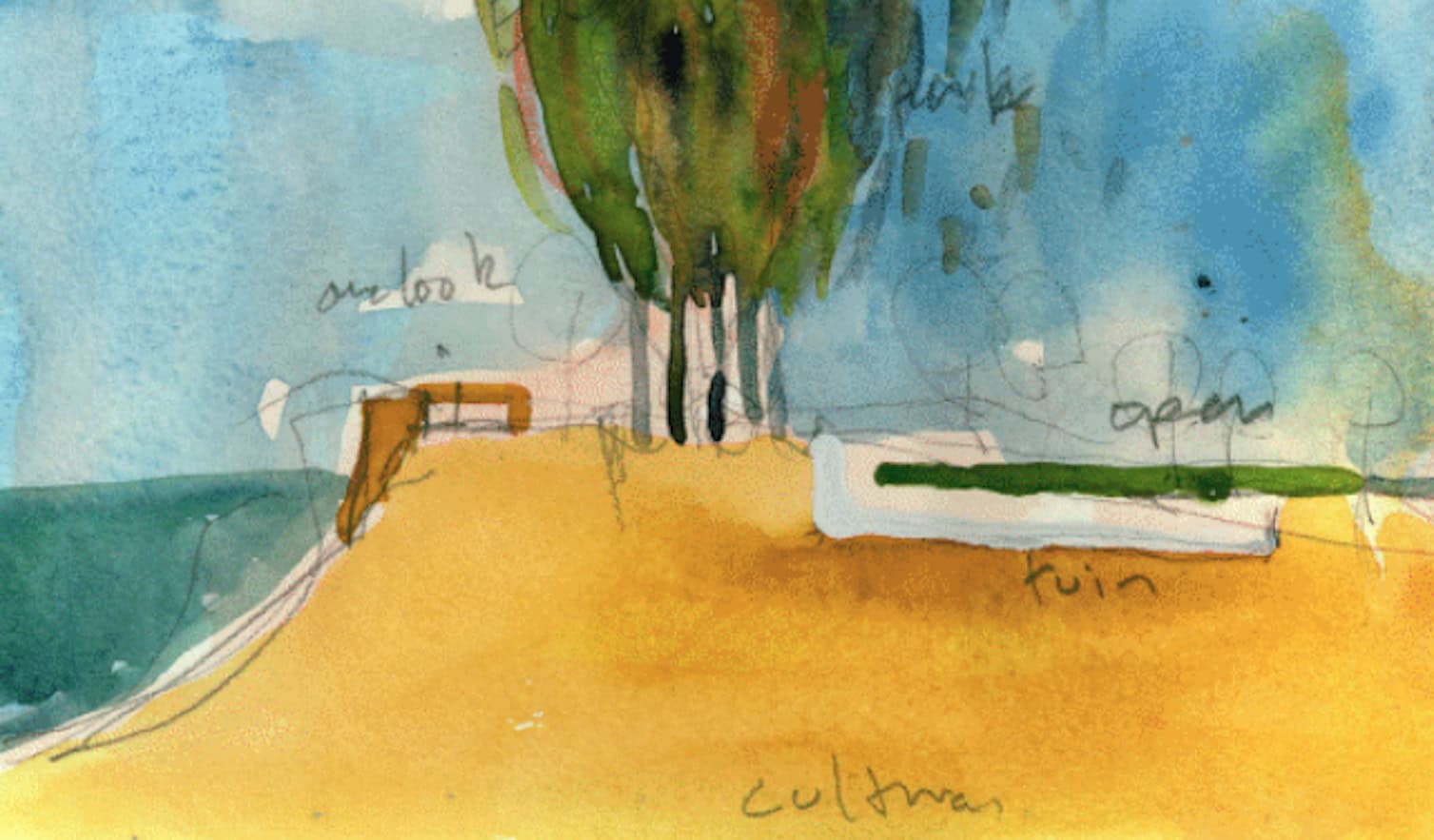

WH: Our park is linear, and on one end, there was a typical round water tower, which I wanted to save, and on the other, there was a second water tank that was actually a building. I spent time in Italy at the American Academy doing a lot of archeological digs, and the water tank reminded me of a Roman aqueduct and water supplies there. So the idea was–what if we could save this ruin that we could actually occupy? The early designs had you floating through the ruin as you made your way up, and then when viewing the Bay you’re actually in something of the past that’s architectural. We were able to save one water tank, but we lost the other one up at Signal Hill. We’ve actually left Signal Hill as natural as possible–we want it to be a space that reflects back to the history of it being a goat hill. So, the park is less designed at one end and a more highly subtracted design on the other end.

There’s a synergy between nature and design in landscape architecture. Can you reflect on a personal connection to nature that has inspired your designs throughout your career?

WH: I grew up in the South in North Carolina and spent my childhood summers at my uncle’s farm, so agriculture was a big part of my early upbringing. I’m not romantic about the green stuff–I’m interested in how we live in it. That’s probably the more powerful aspect of my work–this focus on culture and how landscape is a product of culture.

How does sustainability play a role in your designs?

WH: I’d like to think of sustainability differently, in that we didn’t remove everything, which means that we didn’t have to relocate excess materials somewhere else. So, we have a very low impact. This idea of change, change, change, and throwing things away is not sustainable. I think it’s a misunderstanding to think that the green landscape can take care of itself. For us, the sustainable aspect was, again, being able to not remove everything and instead work with what’s there. I think if more people work with what’s there, we will get to a sustainable future faster.

Your approach clearly, and intentionally preserves and enhances the existing elements on Yerba Buena Island. Could you elaborate on how this preservation benefits and adds value to the space?

WH: Definitely low water use. We propagated a cultural landscape, a landscape that’s familiar to this environment, like perennial grasses, cypress trees, etc., which we know will survive in this place. To me, that’s a form of sustainability.

So at the hilltop park, there’s Point of Infinity, there’s a dog park coming, and more. What part of the park stands out as your favorite or what resonates the most with you about this space?

WH: The water tank. (Laughs) If we had lost the water tank, to me, there wouldn’t be anything there. It really does create the syntax for how one sees the place and how one can interpret it. Again, there’s something about occupying something that’s been in place longer than you’ve been on the planet; about inhabiting something from yesterday.

How do you feel this hilltop park contributes to the well-being of the community in a primarily urban environment like San Francisco?

WH: Every time we make new places we tend to start over. So there’s no connection then to the people who were in the space before. I do think this idea of constantly erasing to begin again does something to us to a certain degree. This idea of memory has always fascinated me: “How can I have connections to a larger set of meanings?” In a project, I always like to leave something from the previous. Over time, you build the story. The story doesn’t just happen when you arrive, the story is in constant cultivation, and we find that history is this element when you think about places that are valued. Some of our most loved neighborhoods always have something old in them–like cobblestone roads or a Victorian build. Now, when you go to the hilltop park, it really has this power to it. It almost feels like I’m in the Mediterranean. I have that feeling of occupation–I don’t feel like I’m the first person there. These historical layers contribute to our well-being.

Can you share how elements such as the cobblestone streets or any unique textures or defining features at Yerba Buena Island resonate with the island’s rich history and your approach to designing spaces that reflect it?

WH: Oh, yeah. We were able to keep the original walls of the water tank, which was a building. When you walk on the inside, you can actually see the buttresses of it. It has this kind of gutsiness to it, and the other beautiful thing that I love is that in order to remove the waterproofing, the contractors literally had to chip away at it. The chipping actually created these marks, and the marks are all different, and in each section, it looked like little bird’s feet. There are these layers of history and time.

You found such an interesting way to include humans in that landscape–like we’re part of nature as well, and you marry those two.

WH: Yeah, the only reason why I’m making the park is for people. One of my mentors told me, “Walter, we’re only here because of change.” We’re trying to say we’re all in this thing together. When it was a military base, it was just as important as when the natives were here. People occupied this place, and their occupation has shaped it, and it’s actually giving people memories. I really love that someone can come back now who lived on the island and go, “Oh, that used to be the water tank.” And that, to me, is profound. People are nostalgic for certain things in their past, and we don’t try to recreate them. But we have that reflexivity about why people want to go there. And so giving them a little bit every now and then really does help us, sociologically and psychologically, as we think about our relationship with places.